In late March, Steven Stamkos noticed pain and swelling in his right arm after a game against the Canadiens. A lot of athletes would have ignored the symptoms. but a lot of athletes don’t have teammates who’d experienced the exact same thing and been diagnosed with a blood clot. Stamkos turned out to have the same condition as Lightning goaltender Andrei Vasilevskiy — thoracic outlet syndrome.

Stamkos returned to the ice this week with the Lightning. He's going through drills but that doesn't mean he's going to return to the ice anytime soon for Tampa Bay.

Thoracic what? And what's with the blood clots?

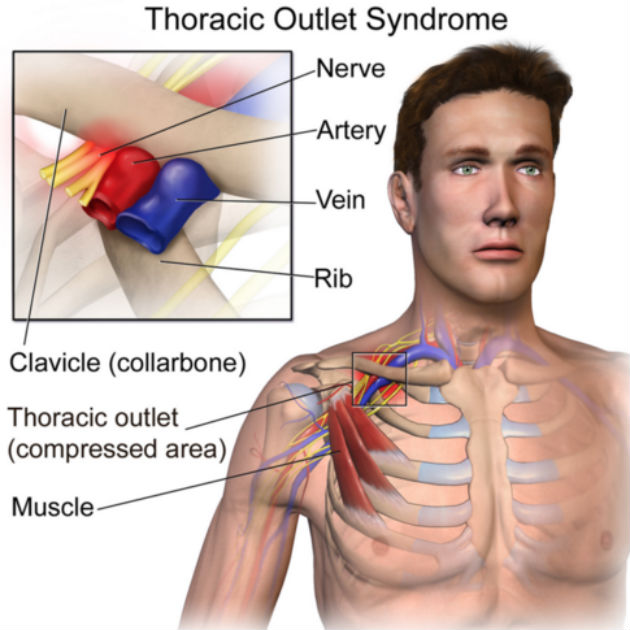

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a condition that happens when structures in the upper chest/shoulder put pressure on important things like the nerves, artery or vein that supply the arm. There can be different causes — an extra rib, scar tissue, trauma, repetitive stress from overhead movements, even certain tumors. The compression can lead to numbness or tingling in the arm, muscle weakness, compromised blood supply and even blood clots in the area.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In Stamkos' case, compression between a rib and the clavicle caused the issue and led to a blood clot, which is what caused his symptoms. While Stamkos is not the first NHL player to deal with clot issues, he and Vasilevskiy differ from several of the others in that their issues were fixable and temporary. This is in stark contrast to Kimmo Timonen and Pascal Dupuis, both now retired. Timonen has Protein C deficiency, a hereditary clotting disorder requiring lifelong anticoagulation (blood thinners). Dupuis developed a blood clot in his leg (also known as deep vein thrombosis, or DVT) after knee surgery that led to clots in his lungs (also known as a pulmonary embolus, or PE). While some players can overcome DVTs with a few months of blood thinners, Dupuis had recurrent PEs and eventually decided to retire.

MORE: Longest Stanley Cup playoff games | The Rangers' future

Stamkos and Vasilevskiy both had procedures to remove their uppermost rib, which relieves the pressure on the structures underneath and resolves the associated symptoms. The problem is that blood thinners still are a component of the treatment. Not only do you have to recover from having a bone removed, you need one to three (or more) months of anticoagulation, which makes playing hockey a bad idea.

But Timonen and Dupuis played on blood thinners ...

The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology established task forces to create guidelines for athletes with cardiovascular conditions. Their recommendation is that athletes should not participate in sports in which impact is expected (like hockey) because of the increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage (brain bleeding after injury). Since playing hockey while anticoagulated is clearly a bad idea, the NHL has come up with a protocol that avoids the increased risk of bleeding by using a certain medication and dosing schedule.

Traditionally, people are put on warfarin (brand name Coumadin) when they have DVTs. That's the medication on which Dupuis started. It requires scheduled blood tests to make sure dosage is adequate, it limits what people can eat because certain foods limit its effectiveness, and people bleed and bruise more than usual while taking it. There are other, newer anticoagulants out there that don't have the dietary restrictions or blood test requirements, such as rivaroxaban (brand name Xarelto), which is the medication NASCAR driver Brian Vickers took after his DVT and PE episodes and which eventually became his sponsor.

MORE: Timonen retires a Stanley Cup champion

The NHL's protocol uses neither of these. Yet another option is enoxaparin (brand name Lovenox), which is given by injection. Lovenox is the first medication given to a patient with a DVT or PE because warfarin takes a few days to kick in when people start taking it. Most don't stay on Lovenox long term because giving oneself shots sucks, especially if there's a non-needle option. The other issue is that Lovenox is short-acting — it reaches peak effectiveness about four hours after the injection, which must be done daily to prevent DVTs (twice daily to treat them in the acute phase). That issue is what makes it ideal for anticoagulated hockey players who want to keep playing.

On game days Timonen and Dupuis would skip their Lovenox injection, reducing the risk of bleeding if they should suffer an injury. In Dupuis' case, it didn't work out. Every time he had symptoms that could possibly be a PE, a series of tests would result, the gold standard of which is CT angiography, which carries a not insignificant amount of radiation.

In a statement, Penguins team physician Dr. Dharmesh Vyas said that the risk of playing and the long-term potential side effects of the tests weren't in Dupuis' best interests, so he retired.

Players with a history of clots and a need for anticoagulation have to weigh the benefit of not having a brain bleed from bumping their heads on the ice vs. the risk of taking a break in anticoagulation. For Dupuis, it wasn't a good fit.

What does that have to do with Stamkos?

Probably nothing. He doesn't need long-term anticoagulation. The problem was fixed when the rib was removed. He's back skating in a red, non-contact jersey, but Lightning coach Jon Cooper has said he doesn't expect him back anytime soon, and Stamkos has been careful to point out there is no real timeline for him to come off the anticoagulants. The real question is whether we'll see him again this season. At the moment it looks like that would require a deep playoff run for the Bolts. Even then, the post-op two-month mark is June 4, and that seems ambitious for someone who's now one rib short of where he started.

Does this episode affect Stamkos' future value given that he can become a free agent this summer? Probably not. Once he comes off the anticoagulants and fully rehabs, he should be back where he was in terms of strength and ability. The right arm connects to the chest by way of the shoulder, and the procedure involves all of those in some capacity. The beauty (and the pain in the butt) of the shoulder is that it's an incredibly complicated joint with a lot of moving parts. Taking out a rib and a little muscle or two shouldn't affect the right arm, because there's plenty in there to take up the slack. Tampa Bay fans have nothing to panic about, at least as far as Stamkos' health is concerned.

Dr. Jo Innes is a contributor for Sporting News. Follow her on Twitter: @JoNana.